In orbit, every fraction of degree matters. That is why nanosatellites use an advanced ADCS (Attitude Determination and Control System), which is responsible for maintaining the correct attitude in space. ADCS integrates data from sensors and actuators to control three axes of rotation:

- Roll – rotation around the longitudinal axis,

- Pitch – forward and backward lean,

- Yaw – turning left and right.

To minimize aerodynamic drag and thereby extend the satellite’s operational lifetime, the NADIR mode is used as one of the satellite’s primary operational modes in orbit. In this mode, the satellite maintains its attitude towards Earth. It requires very low angular velocities of 0.1°/s and small roll, pitch, and yaw deviations.

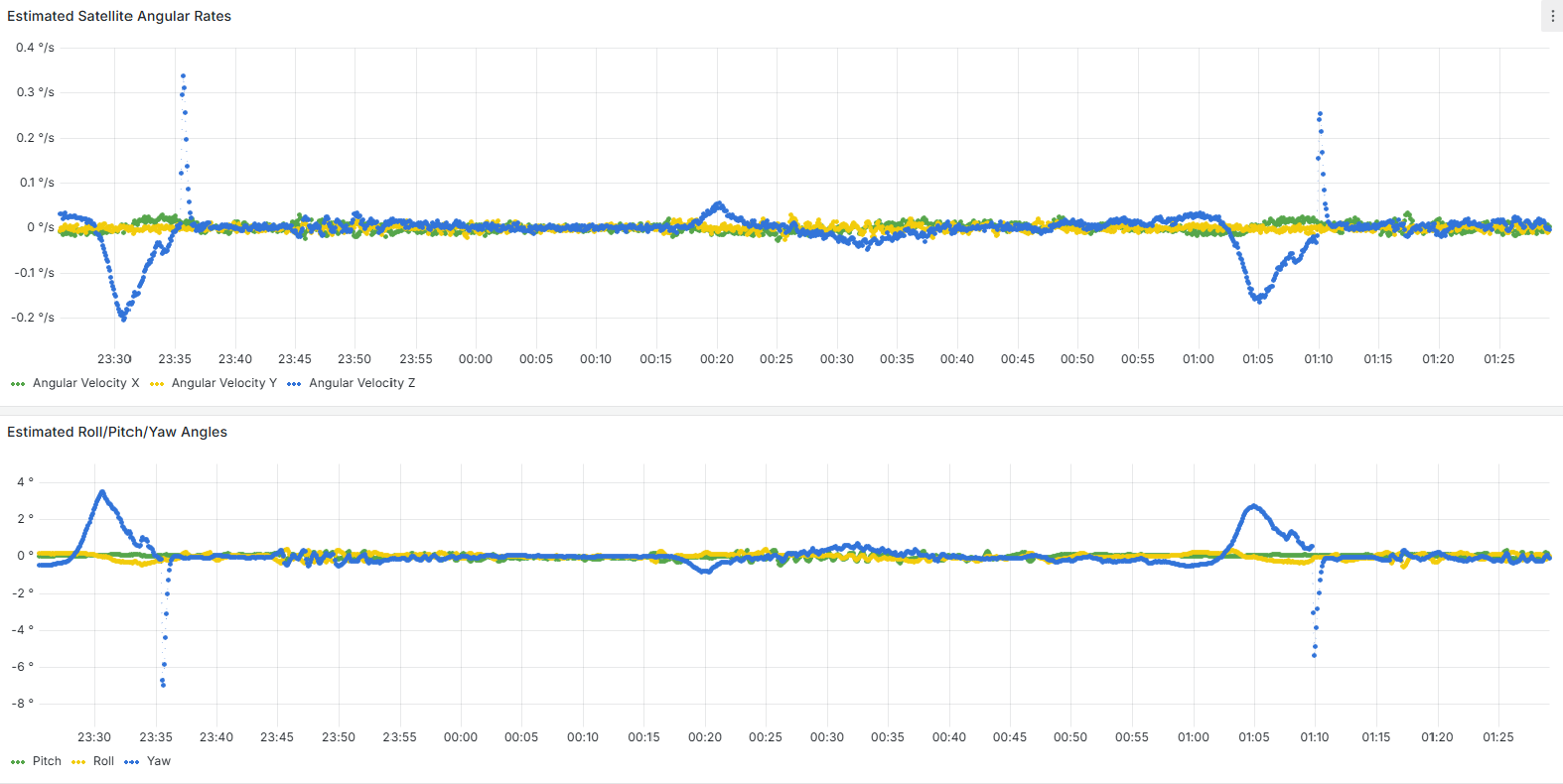

The chart below shows what precise attitude control looks like in practice.

The top panel shows the angular velocities in three axes (Roll – green, Pitch – yellow, Yaw – blue), which in nadir mode remain close to zero – approximately ±0.1°/s. This confirms the stability of the satellite.

The bottom panel shows approximate attitude angles. Periodic pulses visible mainly in the yaw axis are associated with transitions between eclipse and sunlit conditions and the activation of the Fine Sun Sensor (FSS), which provides precise data to the attitude estimator. The estimator makes corrections after receiving the data.

This is how NADIR mode works in numbers – the foundation for Earth Observation mission operations.

.jpg)

Na orbicie każdy ułamek stopnia ma znaczenie. Dlatego nanosatelity korzystają z zaawansowanych systemów określania i zadawania orientacji (ang. ADCS - Attitude Determination and Control System), które odpowiadają za identyfikację i utrzymanie właściwej orientacji w przestrzeni. ADCS integruje dane z czujników i steruje aktuatorami, aby realizować orientację satelity względem trzech osi obrotu. W nomenklaturze inżynierii kosmicznej i lotniczej rozróżniamy i definiujemy:

- pochylenie (eng. Pitch) – obrót w lewo i prawo,

- przechył (eng. Roll) – obrót w przód i w tył,

- odchylenie (eng. Yaw) – skręt w lewo i prawo.

W opisywanym przypadku tryb NADIR używany jest w taki sposób, aby zminimalizować opór aerodynamiczny w celu wydłużenia misji i jednocześnie zapewniając efektywne wykonywanie tejże misji. Tryb NADIR, utrzymujący orientację satelity skierowaną ku Ziemi, wymaga stabilności, bardzo małych prędkości kątowych rzędu 0,1°/s i niewielkich odchyleń roll, pitch i yaw.

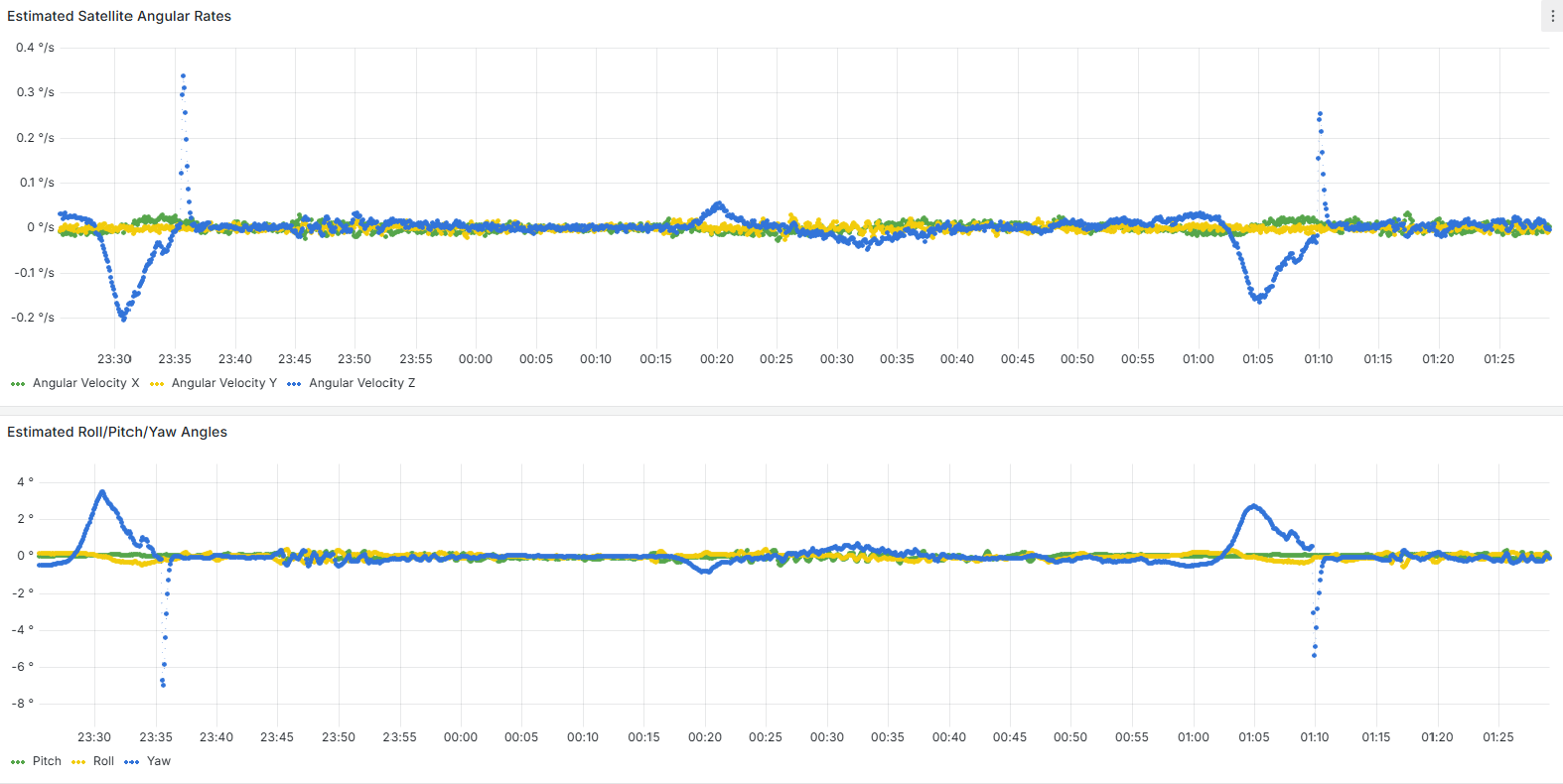

Na wykresie poniżej prezentujemy, jak wygląda precyzyjna kontrola orientacji w praktyce.

Górny panel pokazuje prędkości kątowe w trzech osiach (przechył – zielony, pochylenie – żółty, odchylenie - niebieski), które w trybie nadir utrzymują się blisko zera – około ±0,1°/s. To potwierdza stabilną orientację satelity.

Dolny panel przedstawia przybliżone kąty orientacji. Okresowe impulsy widoczne głównie w osi yaw są związane z przejściami pomiędzy zaćmieniem (eclipse) a oświetleniem przez Słońce (sunlit) i aktywacją dokładnego czujnika Słońca (FSS), który dostarcza precyzyjnych danych do estymatora orientacji. Estymator po uzyskaniu danych dokonuje korekty.

Tak wygląda praca w trybie NADIR w ujęciu liczbowym – fundament dla wszystkich operacji misji obserwacyjnych Ziemi.

.jpg)